- Published on

Why not RDF in the AT Protocol?

- Authors

- Name

- Paul Frazee

- @pfrazee.com

It's a good idea to jot down a couple of notes on our decision-making at Bluesky. These notes won't be extensive.

Also in this series:

Identifying data

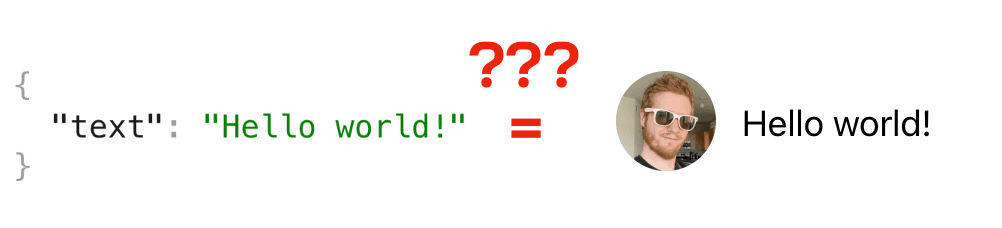

How do you know, when you see a piece of JSON, that it's supposed to be a microblog post?

In traditional client-server apps, you know from the server documentation. The /api/getPost route is documented to return a post.

When you get into multi-vendor scenarios, this model stops working as cleanly. One server may have the /api/getPost route. Another might have the /api/posts/:id route. There may also be differences in how the servers model the post.

This is a problem of semantic and schematic agreement.

- Semantic: what names do we use to identify the types of data.

- Schematic: how do we model the data — or more simply, what fields do we expect and how do we expect them to be defined?

The common answer: RDF

RDF was invented to solve these kinds of problems1. You can see it used in ActivityPub, DIDs, Verifiable Credentials, SOLID, and a variety of other protocols designed for multi-vendor environments.

RDF uses an elegant model of graph triples. Everything gets distilled down into nodes and edges between those nodes.

Suppose you run a GET pfrazee.com request and you get this JSON:

// the output of pfrazee.com

{

name: "Paul Frazee",

job: "Programmer"

}

In the graph model, you'd model it like this:

pfrazee.com --[name]--> "Paul Frazee"

pfrazee.com --[job]--> "Programmer"

RDF then adds a global identifiers. Instead of an ambiguous short word such as "name," it uses a full URI so our graph would look more like this:

pfrazee.com --[schemas.com/name]--> "Paul Frazee"

pfrazee.com --[schemas.com/job]--> "Programmer"

There's no ambiguity because we're relying on the global namespace of DNS.

This solves the semantic question. We never have any questions about what type of data we're looking at.

This also half solves the schematic question because the edges can define the expected value types for the target nodes.

However, because these definitions are per-field, there are some additional work that's necessary to establish the schema in the full "document" sense. If it is important that pfrazee.com output both schemas.com/name and schemas.com/job, then you need to use additional systems inside RDF such as SHACL.

Why not RDF?

RDF is notorious for having a bad developer experience. While it is conceptually elegant, the heavy use of URIs inside the data model clutters a lot of the code.

Even with syntax is designed to simplify the data, it can be verbose and difficult to understand. JSON-LD and Turtle are two examples of this. Most people think they understand JSON-LD but they do not.

An example Turtle document

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> .

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/stuff/1.0/> .

<http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar>

dc:title "RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)" ;

ex:editor [

ex:fullname "Dave Beckett";

ex:homePage <http://purl.org/net/dajobe/>

] .

I think it's fair to say that you can model two separate systems correctly without preplanning thanks to the generality of RDF. However, very few systems natively use a graph model and programmers are not often familiar with it2. The closest mainstream technology might be GraphQL.

I looked very closely at RDF during the AT Proto's initial design phase. One of the initial drafts for our schema system was based on RDF.

My belief is that a highly opinionated language (akin to Turtle or JSON-LD) which drops some of the features of RDF in favor of a more concise language could actually be effective. I ran out of time while exploring this option, and in the interest of pragmatism turned toward other foundations.

In particular, I believe that a document-oriented model is more intuitive for software engineers. The request/response bodies of HTTP and RPC systems are documents. Moreover, ATProto's data model is fundamentally a document store. Therefore, a document-oriented model seemed to be the best choice.

JSON-Schema with namespaces

The second draft of our schema system used JSON-schema, which did not solve any semantic concerns but does solve all of the schematic ones.

To solve the semantic element, we introduced the notion of a namespaced identifier (NSID) which is simply a form of reverse-DNS.

app.bsky.feed.post - A microblog post record

com.atproto.server.createAccount - The RPC route to create an account

We chose reverse-DNS to strongly indicate that a data type was being identified and not a resource.3

For a time, JSON-schema with NSIDs was the entire schema system, but we found ourselves struggling to achieve all of our goals.

- Correctness. In a highly distributed and multi-vendor system, it needs to be easy to maintain agreement on API contracts and data schemas.

- Ease of use. The schema language needs to be approachable, and it needs to be possible to create convenient tooling for & from the schemas.

- Evolvability. The language needs to support changes to the schemas, including from third-parties who are looking to extend the core behavior.

- Specificity. We should aim to eliminate ambiguity about behaviors, even when developers are not in contact with each other.

In a decentralized system, a great deal comes down to communication between parties who do not meet each other. Compatibility is a social question, and the tooling needs to help.

Developers have to predict how each other's software is going to behave. You need to know that whenever you add a new field, you're not going to introduce bugs in other people's software (and visa-versa). Everybody needs to have strong guarantees about how the network will operate in practice so that you can be comfortable writing your own software.

Lexicon

We eventually conceptualized our target as a kind of "d.ts for ATProto" — that is, a type declaration language for all of the interfaces and data-types on the protocol.

We wanted it to translate cleanly into static type systems for generated code, and we wanted runtime validation to be reliable enough that applications would not break due to bad data.

We wanted the validation layer to be expressive enough to include constraints on data (such as string sizes and number ranges).

Lastly, we wanted to address evolvability of the data as it relates to forwards/backwards compatibility as well as the introduction of new behaviors from outside of the original schema authors.

Here's what a declaration looks like:

{

"lexicon": 1,

"id": "app.bsky.feed.like",

"defs": {

"main": {

"type": "record",

"description": "A declaration of a like.",

"key": "tid",

"record": {

"type": "object",

"required": ["subject", "createdAt"],

"properties": {

"subject": { "type": "ref", "ref": "com.atproto.repo.strongRef" },

"createdAt": { "type": "string", "format": "datetime" }

}

}

}

}

}

If you're typescript-minded, you might conceptualize this data model as follows:

import {StrongRef} from '/com/atproto/repo/strongRef'

export class Like extends Record {

subject: StrongRef

createdAt: Date

}

You'll notice that types can be referenced, which is extremely helpful for re-use.

In fact, there's a "union" type which enables multiple referenced types to be used.

{

"lexicon": 1,

"id": "app.bsky.richtext.facet",

"defs": {

"main": {

"type": "object",

"required": ["index", "features"],

"properties": {

"index": { "type": "ref", "ref": "#byteSlice" },

"features": {

"type": "array",

"items": { "type": "union", "refs": ["#mention", "#link"] }

}

}

},

"mention": {

"type": "object",

"description": "A facet feature for actor mentions.",

"required": ["did"],

"properties": {

"did": { "type": "string", "format": "did" }

}

},

"link": {

"type": "object",

"description": "A facet feature for links.",

"required": ["uri"],

"properties": {

"uri": { "type": "string", "format": "uri" }

}

}

"..."

}

}

This translates roughly to the following typescript:

class RichtextFacet {

index: ByteSlice

features: ( Mention | Link )[]

}

class Mention {

did: string

}

class Link {

uri: string

}

When data is transmitted, it uses the $type field to identify its schema. This resolves the union to one of the specified types.

{

$type: 'app.bsky.richtext.facet',

index: {byteStart: 0, byteEnd: 11},

features: [

{

$type: 'app.bsky.richtext.facet#link',

uri: 'https://example.com'

}

]

}

Evolvability

Of the goals stated, evolvability is the interesting one. Using namespaced IDs is somewhat pointless if you can simply define all the schemas in the core protocol spec and call it a day.

What this requires is points of extension. The union (above) ends up being one of the most common extension points, because they're actually "open" unions. That is, the actual definition of the facet schema is more like this:

class RichtextFacet {

index: ByteSlice

features: ( Mention | Link | { [k: string]: unknown } )[]

}

This means that basically any schema can be used there. The enumerated types are more of a suggestion.

If we wanted to add a hashtag type, we would do so like this:

{

$type: 'app.bsky.richtext.facet',

index: {byteStart: 0, byteEnd: 7},

features: [

{

$type: 'app.bsky.richtext.facet#tag',

tag: 'atproto'

}

]

}

Past that, the other significant point of evolvability (that's in practice now) is the RPC methods. New ones can be defined, returning new schemas, and so on.

All of this happens within the constraints of maintaining forward and backward compatibility of software that's actually in production, and you can hear more of my thoughts on this in my talk on Schema Negotation.

Closing thoughts

This isn't an extensive write-up, but it is a quick view into the thinking behind Lexicon. You should take a look at the Lexicon spec if you want to dig a little deeper, and we'll write up plenty more in the future.

1 RDF is sufficiently complicated as a topic that I expect I will have gotten some details wrong here. I apologize if so.

2 Before I get 15 programmers telling me how often they use Neo4j — let's just agree that it's not exactly the most common choice.

3 I wasn't exactly enthusiastic about reverse-DNS but I've come to feel ambivalent about it.